“Everyone who remembers his own education remembers teachers, not methods and techniques. The teacher is the heart of the educational system.” —Sydney Hook

I admire great teachers, both the ones of historical renown and those I have known who have guided my education. I am indebted to them both.

At the risk of being impertinent, I have chosen the title of this post for a reason. Would the great teachers of the classical age approve of the course content of current education? Would they agree with the preparation regime which prospective applicants must undergo? Both of these must be addressed if our educational system if to fulfill its promise.

There is a continuing emergency regarding the supply of teachers to our public schools. However, like a dog chasing its own tail, a cabal of university departments of education, state and local credentialing agencies, and institutes allied with all of these continue to build themselves up. These form a complex maze which those who aspire to teach must navigate (and pay for). It is by no accident that teacher shortages have increased and student outcomes have suffered. This is combined with falling public school enrollment in the wake of privatization and lowered attendance due to truancy. There are societal factors as well: the distraction of the media, disaffection with the value of education; the economic struggle of parents which leave them little time to assist their children. Still, the task must continue to support public education and public educators. It is a key foundation of our democracy and is too important to neglect.

This, as they say, is “ripped from the headlines”. Currently there us a standoff between the California Association of Teachers and the Commission on Teacher Credentialing over a bill that would have eliminated teaching performance assessments — the last licensure test California teacher candidates are required to take. The bill was amended in mid-June under pressure from “education advocacy groups” to retain it, but without the requirement that teacher candidates take video clips of classroom instruction and submit lesson plans, student work and written reflections on their practice to prove they are prepared to become teachers. In response to the position that the assessment be ended, the provision was added that the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing convene a working group of teachers, college education faculty and performance assessment experts to review the assessments and recommend changes (more bureaucracy, not less). The revised bill, if passed, would require approval of recommendations from the work group by July 1, 2025, and to implement them within three years from that date. The commission would also be required to make annual reports to the Legislature. Leslie Littman, California Teachers Association vice president, said that the amendments retaining the test were “disappointing” but that the creation of the work group is a positive step toward addressing the concerns that union members have had with the assessment. Proponents of the teacher performance assessments say that eliminating them would have removed a valuable tool for evaluating teacher preparation programs and new teachers. Here it is in “edspeak”: “We know when parents drop kids off at school, the most important thing in front of those kids is that teacher, and they want to make sure … that teacher is prepared to teach effectively, and that’s what the TPAs help do,” said Marshall Tuck, CEO of EdVoice, identified as an “education advocacy organization”. Translation: more resources for the bureaucracy and more hoops to jump through (and pay for) before the teacher arrives in the classroom)

We should listen to the teachers and not the gatekeepers. Many say the test is a waste of time. The original bill was introduced by State Senator Josh Newman, chair of the Senate Education Committee, who said in April that eliminating the assessment would encourage more people to enter the teaching profession, and that it duplicates other requirements teachers must fulfill to earn a credential. This was echoed by K-12 teachers who were overwhelmingly critical, stating that it is too time-consuming, caused anxiety and does not help prepare teachers for the classroom.

This is not the only assessment that teacher candidates must pass. There is a virtual alphabet soup of these that the prospective teacher must pass: either the California Teaching Performance Assessment (CalTPA), the Educative Teaching Performance Assessment (edTPA) or the Fresno Assessment of Student Teachers (FAST) before they can earn a preliminary teaching credential. The tests cost $300 total, or $150 per cycle—more money, more preparation time, fewer candidates.

Here is my take: just as the best preparation for a plumber is plumbing and the best preparation for an auto mechanic is working on cars, the best preparation for teaching is teaching. At the risk of being overly simplistic, “teaching teaches teachers”, or as the Nike slogan says, “just do it”. Just as for the proven value of apprenticeship programs, I am in favor of getting undergraduates to the classroom as soon as possible to work with a seasoned teacher and receive immediate feedback (from teacher and students). This will also help them decide if they are really suited for this line of work. Several universities are folding credentialing requirements into the fourth-year program and are contributing to the solution.

A “streamlined” Teacher Preparation Assessment bill does not mean that the California Teachers Association will not bring its previous elimination demands back. Here is the reaction from the other side (in edspeak): “The hope is that the new bill will now help to streamline and improve the administration and scoring of the Teacher Preparation Assessment to ensure they are an additive, constructive experience for candidates, and that they do not have a disparate impact for candidates of color.” The last statement is a telling one: there is a glaring shortage of teachers from minority and low-income groups. There is a direct line between preparation time and expense and these demographics. Students of all ethnic and economic backgrounds deserve to have teachers like them with whom they can identify. I am interested to see if the proposed changes move the needle.

We have all seen one-room schoolhouses. Historians and preservationists seek to restore them, often furnished with the realia of desks, books, and classroom items to give the visitor a vivid view of the past. How, you may ask, did education occur with minimal books and resources and many grades seated in the same room, taught by a teacher with few resources, whose experience was only slightly beyond that of the graduates he or she was expected to produce? The outcome may seem like a miracle. Well, maybe not really. You see, there was an implied expectation that all of this would happen, and it did: many went on to higher study and many more went on from high school (or less) to successful careers.

One of the buzzwords of pedagogy is “student-centered learning”—empowering the student to be responsible for his or her own results. This is a mantra often recited but not always followed. Teacher preparation is important, but learning depends on the student. In the face of this, the teacher preparation regime tends to be top-heavy on what teachers must or must not do and will become increasingly so in the absence of reform.

Moving on to reading, there is an amazing divergence of opinion regarding the best method of instruction. Briefly stated, there is systematic phonics instruction (called the “science of reading” in current legislation) versus the whole language approach, where students concentrate on the meaning and context of words rather than decoding them. Both of these constitute “the reading wars”, for which no end is in sight. Sadly, the number of students not reading at grade level is a cause for alarm. Yes, there are societal factors, but these are not an acceptable excuse. The most effective teaching strategy must be chosen, validated by results.

In my final years of teaching I noticed a change in the textbooks which appeared in new editions. They were redesigned with bright colors, text boxes, and abundant graphics to “resemble a computer screen”. Perhaps they were more interesting, but at the sacrifice of focus and attention. The benefits of reading printed versus onscreen text have proven to be superior. A “computer like” edition is scattered and fragmented, and concentration suffers. It may create profit for publishers, but does it benefit students?

Our educational culture appears to be rediscovering what was largely abandoned in the rush toward newer course content and competencies. Classes in the “practical arts” which had once disappeared (along with some who taught them) are now reappearing. These subjects formed some of my most interesting experiences in school but are more than just that. All of them have the power to boost cognitive abilities in a variety of ways. They also address different learning styles, helping more students to achieve success and self-esteem. Among these are:

(1) Art classes, which help develop fine motor skills in the creation of a project, communication skills if the project is that of a time, creativity as well as self-confidence, cultural and aesthetic appreciation, and critical thinking skills as students create, make decisions, and take risks. In a multi-cultural classroom, art creates a cultural bridge. (2) Music classes, which build self-confidence through performance, require teamwork skills in a band or choir. In addition, the study of music reinforces language skills along with memory and retention, improves motor skills through playing an instrument or singing, and aids learning overall by blocking out distractions and improving memory and concentration. (3) Cursive writing, deemed obsolete in an era of keyboarding, disappeared from the curriculum but its value is now being rediscovered. The very act of connecting letters together activates different neurological pathways and creates a flow of thought as well as of words. This, in turn, aids retention as the barrier between thought and content is minimized. Written notes are remembered better than typed ones, as the writer must be more selective as to what to write down. Spelling is improved. As with art and music, fine motor skills are developed. The ability to read written documents in their original form is an added benefit. (4) Reading of printed material improves memory retention. It is far too easy to scroll through a screen and “half-read” the material at hand. If for no other reason, choosing to read books to balance one’s intellectual intake is a wise decision. (5) the elimination of shop classes has had a direct effect, both in the shortage of skilled trades personnel and in the great number of misplaced students who never wanted to be on the college track in the first place. A recent Facebook post by Shaun Nelson hits the nail on the head (Do you like my vocational reference?) “Trades were removed from high schools in the ever-growing pursuit of ‘everyone goes to college’… so now a lot of trades are screaming for replacements because people want to retire.” As in the opening argument, the educational/credentialing establishment can once more be faulted with creating a lesser class of high school vocational instructors with reduced compensation and job security. Those who could impart valuable skills to students were discouraged from doing so by credentialing barriers. Fortunately, some community colleges are picking up the slack with programs aligned to, and created with, the cooperation of the business community. We still need to bring back shop classes in middle schools and high schools to provide an introduction to these vocations. As an added benefit, students develop problem solving, creative thinking, hand-eye coordination, and the ability to transform an abstract concept into a finished project. “Learning through doing” benefits the tactile learner whose strengths lie in this area. (6) Finally, Home Economics must be included. These classes, once the criticized by the women’s liberation movement as fostering subservience, have been rediscovered (and re-branded as Family and Consumer Sciences) as helping all students create a self-sufficient life and financial well-being.

Vocational education is making a comeback at the high school level, and schools which have implemented it have shown great success. Its popularity is driven by the skyrocketing increase in college tuition, coupled with the decreasing gap between professional compensation and that of the skilled trades. This is driven by increased demand. Generaton Z has been described as the “toolbelt generation”, and many have lost faith in college. Roughly half of high schoolers now believe a high school degree, trade program, two-year degree or other type of enrichment program is the highest level of education needed for their anticipated career path. Even more believe that on-the-job experience is more beneficial than a degree. A two-track option would better fit the needs of students, and empower them to make choices regarding their future.

I graduated from what is now called a “Classical High School”, though I didn’t know it at the time. While descriptions vary, a good working definition might be an emphasis upon content-rich literature, a deep understanding of the fundamental principles of math and science, and a deep appreciation of art and music. It differs from what may be called modern education in that the latter teaches a common core (currently widespread in education circles), verified by standardized test scores. Classical education focuses instead on teaching all students the tools necessary for self-education. Specifically, some institutions or school systems require a minimum of two years of foreign language and two years of the arts, though these may differ. Some place a special emphasis upon Latin, which is making a resurgence after nearly dropping off the map. It promises great benefits, but is perhaps too great a leap in many cases. I would like to suggest a modification to the “pure” Classical model, as teachers with the necessary Latin background may be hard to find. A useful alternative is the study of Latin and Greek word roots, an eminently practical and useful unit which can be smoothly integrated into English courses. I mention this because I was introduced to Greek and Latin word roots in the first semester of seventh grade (and yes, a middle school can also receive a Classical designation). It has stayed with me through the succeeding years of my academic life, and I have expanded upon it with additional study. I have employed it teaching English as a Second Language students who were preparing for college, as they needed to acquire skill in “decoding” words to anticipate their meanings.

As stated, the end goal of Classical education is to teach students learning how to learn, fostering critical thinking and analytical skills. If there is a drawback, it could be said to be a reliance upon memorization, narration, and dictation (although these do not occur consistently, or in all cases). It can only be a weakness if the individual who relies too much upon it does so at the neglect of critical thinking skills. Some express their concern over its relevance to modern life and its lack of emphasis on practical skills, but this may be remedied by the reintroduction of the “practical arts” classes previously mentioned.

Here I must issue a warning, as some players in the current Classical Education movement are aggressively pursuing Christian nationalist, Eurocentric goals to the exclusion of students of other cultural groups and religions. Its use as a weapon for cultural superiority calls for a return to earlier conditions which were not, and cannot be, inclusive of all learners. I will not name them specifically, but they are easy to identify. It should come of no surprise that they have political as well as educational motives. It is not what this country is, or should be, about. These inequalities do not have to be. While rooted in Western tradition, there is no reason why this should be exclusively so. Left in an unbalanced state, Classical Education can lead to ethnocentrism, acculturation, xenophobia, and other negative tendencies (I looked up these meanings and you should too). These, I feel, can be mitigated by (1) dialogue (the Socratic Method), a continued probing led by the teacher to explore underlying beliefs that shape students’ views and opinions; and (2) an inclusive student body, largely absent in earlier eras. This is a task for the community at large. For too many years, practices such as redlining and restrictive housing covenants have supported segregation, to the detriment of the community as a whole. There has been progress (the 1965 Civil Rights Act, the Fair Employment and Housing Act) but challenges still remain. Here, too, the internet as a research tool can serve a beneficial purpose as a “democratizer”, exposing the student to a far greater intellectual environment than was previously possible.

School boards implement policy, and the subject of local politics cannot be overlooked. School board elections may seem insignificant, but are extremely important. Here is where some people that you would not like to see in higher office get their start. They come with an agenda, often cloaked in deceptive terms such as “parental rights”, and are often heavily financed, which (amazingly) has no limit in California. The public school system becomes a battleground, and often suffers as a result, not only from their agenda but from financial mismanagement and wasted resources. We the community members, the parents, the voters, should be wary indeed.

For those who wish to investigate further options, I would point you to three essential documents, one which emphasizes the “pure” Classical approach and two which move beyond it. The first is a 1947 essay (available online for those who wish to download a copy) for those who would like to take a deeper look at the Classical model. In The Lost Tools of Learning, British author Dorothy Sayers remarks on the paradox of widespread literacy being accompanied by the rise of propaganda and advertising, the seeming inability of the public to distinguish truth from misinformation, and what she identified as the chief failure of modern schooling: “Although we often succeed in teaching our pupils ‘subjects,’ we fail lamentably…in teaching them how to think.” To reverse this confusion, she argued, educators needed to rediscover the educational program pioneered in the ancient world and ubiquitous in European schooling for a thousand years: The trivium, a three-part sequence of grammar, logic and rhetoric. along with the related quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, make up what were historically known as the liberal arts, and form much of the substance of the revived classical education movement. Its appeal to the families and teachers drawn to it lies in its antique origins, which represent a sturdier basis of learning than the constant progression of newer interventions and orthodoxies that have emerged in recent decades, and which achieve currency (and profitability) by their newness and not their true value. Again, a true Classical model may be difficult to implement but adaptation of its elements is worthy of consideration.

The second document (available in book or .pdf form) is teacher and philosopher Mortimer J. Adler’s The Paidaeia Proposal. It is a system of liberal education intended for all children, including those who will never attend a university. Adler believed the only preparation necessary for vocational work is “learning how to learn”, since many skilled jobs would be disappearing. This is a valid point: compared with jobs of prior eras, where a worker often worked the same job for life, today’s student is actually preparing for jobs which do not yet exist, but whose skills may be acquired by accessing the tools of learning.

The essence of Adler’s proposal involved three necessary types of learning (and teaching): knowing what, knowing how, and knowing why. In a departure from the Classical model, he proposed a curriculum framework featuring the “three pillars of teaching”: the acquisition of knowledge (didactic teaching, or lectures), the cultivation of skills (not necessarily for a vocational purpose, but to acquire the mental agility of learning with one’s hands), and the understanding of ideas and values. His proposal also included an introduction to the world of work.

Adler states that the role of the teacher would be to provide and order questions aimed at the development of understanding ideas. Following this, discussion would be open to all possible answers from students in response to the questions. This prevents them from becoming dogmatic. He felt that any teacher who is also a superior learner cannot fail to allow his inspire his students to become lifelong learners as well. This is the student-centered learning upon which all depends. Top-heavy structures which focus on the teacher’s role alone are not the true reality.

Didactic teaching or “coaching” makes an extensive appearance in Benjamin Bloom’s 1956 Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, which has been adapted in many ways. These skills form a hierarchy by categorizing learning objectives into what are called domains of increasing complexity: (in order) remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. The student is to acquire these skills. Briefly put, skills are habits, not memories, and are therefore much more durable.

The educational landscape has diversified from its classical roots. Its many developments hold much progress, but discernment is necessary to chart the right path. The many choices it presents are daunting, even frightening, but we must put ourselves to the task. There is work to do.

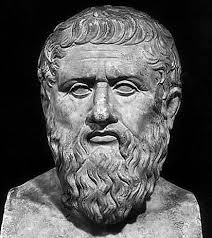

And, just asking, what would Plato say?